As an initial matter, my friend Santi Ruiz just published “50 Thoughts on DOGE.” Well worth reading for anyone, especially those of us who have long been interested in governmental reforms, reducing bureaucracy, etc.

***

Now, back to NIH indirect costs. I’ve written that any attempt by NIH to impose a flat rate on indirect costs could violate both:

- congressional language saying “do no such thing,” and

- the federal rules adopted by HHS as to how indirect costs are to be calculated.

But what if Congress stepped aside and then HHS changed those underlying federal rules?

Can HHS even do that? What else could the administration try to do here?

BACKGROUND

Federal agencies are normally bound by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) in much of what they do. The typical requirements are that when federal agencies issue regulations, they have to give advance notice, consider public comments, and not do anything that is “arbitrary or capricious” (a famous legal standard here).

But there are key exceptions for matters “relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts.” That seems pretty significant, when it comes to NIH grants!

Indeed, it turns out that there is no federal statute that actually requires HHS to use any particular approach to indirect cost rates. For example, under 42 U.S.C. § 241(a)(3), HHS is authorized to “make grants-in-aid to universities, hospitals, laboratories, and other public or private institutions,” but that doesn’t tell us exactly how indirect costs are to be calculated.

So, to be clear—what I’ve written thus far is that NIH/HHS has to stick to the current indirect cost policy, and can’t just unilaterally impose a flat rate on everyone. But all of that assumes that Congress’s instructions and/or the current HHS rule remain in place. Congress could drop its mandate, however, and the current HHS rule as to calculating indirect costs isn’t itself mandated by Congress.

Could HHS just ignore the existing rules? No.

Many Supreme Court cases have held that agencies can’t just ignore current rules, even if those rules weren’t actually required. In United States ex rel. Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U. S. 260 (1954), the Supreme Court held that as long as certain Attorney General regulations remained in place, they had to be followed even though the Attorney General had the discretion to take a different approach. And in United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974), the Supreme Court likewise held that even though the government could “amend or revoke the regulation” as to a Special Prosecutor, it had not done so, and “so long as this regulation remains in force, the Executive Branch is bound by it.” See also Service v. Dulles, 354 U.S. 363, 388 (1957) (“While it is of course true that under the McCarran Rider the Secretary was not obligated to impose upon himself these more rigorous substantive and procedural standards, neither was he prohibited from doing so, as we have already held, and having done so he could not, so long as the Regulations remained unchanged, proceed without regard to them.”).

But if an agency lawfully changes its rules, that is a different scenario.

How were current indirect cost rules enacted?

In 2014, the Obama Administration launched a uniform set of requirements for grants and contracts across the federal government (often called the “Uniform Guidance”). It was a massive effort, and was published in the Federal Register in December 2014 (79 Fed. Reg. 75871) (full text here). The express goal was to “reduce administrative burden and risk of waste, fraud, and abuse for the approximately $600 billion per year awarded in Federal financial assistance.”

HHS sought comments on how to implement these federal-wide regulations, and responded nearly 2 years later with a rule that incorporated comments while still implementing the overall federal approach (see HHS, RIN 0991-AC06, Dec. 12, 2016, full text here). All of that was embodied at 45 C.F.R. Part 75.

All of that said, as of October 2024, HHS issued a new rule that basically abandoned 45 C.F.R. Part 75, and instead just adopts the overall federal-wide approach, that is, “OMB’s Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, to include 12 existing HHS-specific modifications.”

At the same time (that is, in October 2024), the White House OMB issued a new and revised version of the Uniform Guidance for grants and contracts.

That is the regulation that will now apply to HHS and NIH. (PS: much of 2 CFR had already been incorporated into the Terms and Conditions of NIH grants prior to 2024.)

Does HHS have to obey the Administrative Procedure Act when it comes to grants, or not?

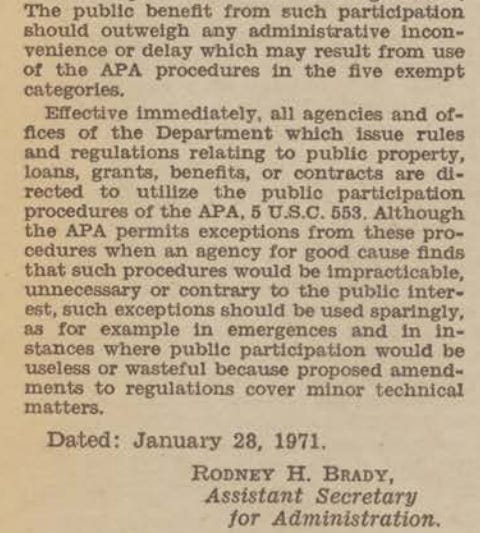

Over 50 years ago, the precursor to HHS (the Department of Health, Education and Welfare) published a policy stating that even though the APA’s requirements don’t apply to grants, the agency would nonetheless keep using the “public participation procedures of the APA.”

The rationale was that it made sense to get public comment on all the grants/contracts that HHS engages in (this includes NIH, FDA, CDC, Medicare, Medicaid, and more).

That policy has been in place ever since—until a few days ago.

In this Federal Register notice, HHS has now said that this 1971 policy is rescinded, because it is “contrary to the efficient operation of the Department, and impede the Department’s flexibility to adapt quickly to legal and policy mandates.”

In theory, the Good Science Project emphatically agrees with this new development.

After all, if we want to reduce bureaucracy for federally-funded science (which the Good Science Project has been pushing for years), one of the easiest ways is to stop imposing additional bureaucracy that isn’t even legally required in the first place!

However, some have speculated that this HHS change might be a back door to letting NIH change how it handles indirect costs. After all, that very 1971 policy was cited in support of legal challenges to the recent attempt to change NIH indirect costs.

If that is part of HHS’s goal here, there are a few questions:

Can HHS reverse the 1971 policy about seeking public input where not required by law?

I think so. There is no legal obligation to do more than the law requires. (As to substantive issues like funding, courts could point to reliance interest—as discussed below—but if the only issue is whether and how HHS seeks public comment on grant policies, it would be more difficult to claim that anyone has a strong reliance interest in being able to submit public comments on any future regulatory change.)

Can HHS just unilaterally reverse all of the extensive cost accounting rules and then impose a flat indirect cost rate on NIH grants?

Probably not.

Remember, the origin of HHS’s regulations as to indirect costs was not HHS itself, but the White House Office of Management and Budget. The original 2014 rule made clear that departments such as HHS would have to act in accordance with the White House’s overarching rule, and that any exceptions would have to be approved by the White House:

With respect to the implementing regulations that Federal awarding

agencies are issuing, any agencies that have received OMB approval for

an exception to the Uniform Guidance have included the resulting

language in their regulations. OMB has only approved exceptions to the

Uniform Guidance where they are consistent with existing policy.

Further, agencies are providing additional language beyond that

included in 2 CFR part 200, consistent with their existing policy, to

provide more detail with respect to how they intend to implement the

policy, where appropriate. Agencies are not making new policy with this

interim final rule; all regulatory language included here should be

consistent with either the policies in the Uniform Guidance or the

agencies' existing policies and practices.Under the current federal-wide rule:

- “Federal agencies must apply [these rules] to non-Federal entities unless a particular section of this part or Federal statute provides otherwise,” 2 C.F.R. 200.101(a)(2).

- “Negotiated indirect cost rates must be accepted by all Federal agencies,” 2 C.F.R. 200.414

- Agencies can only “allow exceptions to requirements of this part on a case-by-case basis for individual Federal awards, recipients, or subrecipients,” 2 C.F.R. 200.102(c).

Moreover, under the Single Audit Act (31 U.S.C. §§ 7501-7507), federal audits of grant recipients are deeply tied to the Uniform Guidance (which refers to that Act many times).

Can HHS just come up with completely new indirect cost rules for NIH, while ignoring federal-wide rules and statutes? Almost certainly not.

What if the White House OMB tried to modify the Uniform Guidance?

I wouldn’t be surprised if the White House is already planning to do exactly that. (Given current trends, I’d be more surprised if they weren’t planning to do so.)

But it would still be difficult to impose a flat indirect rate of 15% on federal research grantees. That would require overturning basically everything about the Uniform Guidance so as to ignore any principle of accounting or costs.

In several cases, the Supreme Court has held that when an agency changes its regulatory approach, it needs to provide a “more detailed justification than what would suffice for a new policy created on a blank slate,” especially when a “prior policy has engendered serious reliance interests that must be taken into account.” FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 556 U.S. 502 (2009); see also Smiley v. Citibank (South Dakota), 517 U.S. 735, 742 (1996) (noting that agency changes that do not “take account of legitimate reliance on prior interpretation” can be arbitrary and capricious).

For obvious reasons, universities and academic medical centers could argue that they have spent the past several decades erecting new buildings, hiring staff, and creating professorships over decades in reliance on regular negotiations with the federal government as to how indirect costs will be paid.

Indirect costs on federal grants haven’t been limited to 15% for over 60 years now, and as I discussed in an earlier piece, the growth in indirect costs has been significantly driven by the explosion in federal regulation over the past few decades.

If the White House OMB tried to impose a drastic limitation on indirect costs that:

- wasn’t based on any actual costs or principles of accounting,

- ignored the regulatory burden created by hundreds of federal regulations, and

- jerked the rug out from under any organization that relied on the federal government’s word for the past 60 years,

I suspect that courts would find such an action to be arbitrary and capricious.

What Can We Expect Next?

If the administration wants to address indirect costs in a productive way that isn’t as likely to be struck down in courts, here’s a possible approach:

- Work to amend 2 C.F.R. Part 200, going through the usual notice-and-comment process. This will take some time, but will be much more defensible in court than an order with zero evidentiary basis that takes effect the next business day.

- Try to bring more transparency to the entire process, such that it is more obvious to the taxpayer how funds are flowing to universities and academic medical centers.

- Many folks have cited Harvard’s indirect rate of 69%. There is almost nothing in Harvard’s indirect cost agreement that would explain why the rate is that high. If that rate is indeed justified, more transparency would be in everyone’s interest.

- In the interest of government efficiency, we should focus on reducing the hundreds of federal regulations that have accumulated over decades, and that are driving many of the indirect costs at hand.

- It makes no sense to limit indirect costs while leaving place hundreds of regulations that mandate universities to spend money on administrators, i.e., indirect costs.

- Phase in any new limitations or changes over a few years, so that institutions and scientists have time to adjust.

- If your mortgage or rent went up by $1,000 a month starting tomorrow, that would be much more trouble than if you got advance notice that the price increase would take place over the next 3 years.

UPDATE:

Since I drafted all the above, a federal district court in Massachusetts just granted a nationwide preliminary injunction against the NIH’s indirect cost limitation. The court’s decision largely agrees with everything I’ve written about the Congressional language and about the existing rule that allows for limited exceptions for certain grants. The decision also has a lengthy passage (pages 37-43) exploring all of the reliance interests at stake. Interestingly, the court holds that the 1971 waiver is still in effect such that the NIH needs to use the notice and comment process—but it’s not clear how that portion of the decision will hold up given that HHS has now officially disavowed that 1971 waiver.