by Stuart Buck

The Paperwork Reduction Act sounds boring and tedious, but it’s actually quite fascinating: it shows how an effort to improve government can ironically become one of the biggest obstacles to government reform.

In the interest of reducing paperwork on the part of citizens, the Paperwork Reduction Act forces anyone in the federal government to go through an onerous (and paperwork-generating!) process before they can do anything that involves asking what citizens think—even including attempts to reduce paperwork! As Shapiro wrote in his comprehensive 2012 report, “It is a common refrain at federal agencies that the PRA increases paperwork.”

As discussed below, one of the most promising reforms would simply be to raise the statutory threshold to 1,000 people rather than 10 people.

After all, the US is not a rural village of a few hundred people, where it might make sense to scrutinize any government action that creates a few minutes of paperwork (often optional) for a mere 10 people. A nation of 330+ million people should not make decisions on that basis.

We all want to improve how government works—including science and R&D, which is the main goal of the Good Science Project. Paperwork Reduction Act reform should be on the table.

INTRODUCTION

To take a step back, the Paperwork Reduction Act (enacted in 1980) is found at 44 U.S.C. § 3501 and following. The motivation for the Act includes:

- “minimize the paperwork burden for individuals, small businesses, educational and nonprofit institutions,”

- “minimize the cost to the Federal Government of the creation, collection, maintenance, use, dissemination, and disposition of information,” and

- “ensure that information technology is acquired, used, and managed to improve performance of agency missions,” among other things.

The Paperwork Reduction Act also created the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OMB is generally authorized to direct and oversee how federal agencies collect and manage information, while agencies are required to manage information resources so as to “reduce information collection burdens on the public,” “increase program efficiency and effectiveness,” and to “improve the integrity, quality, and utility of information to all users within and outside the agency.”

Not all of these goals are mutually consistent, as we shall see.

As for the Paperwork Reduction Act process, agencies are not allowed to “conduct or sponsor the collection of information” unless they have first:

- Conducted a thorough review,

- Published a notice in the Federal Register, and evaluated public comments,

- Submitted an Information Collection Review (or ICR) to OMB, and

- Gotten OMB approval (which happens only after a second round of public comments).

How many Information Collection Reviews or ICRs are submitted to OMB every year? In 2022, there were 5,210 submissions from across the federal government (source: a search at Reginfo.gov).

Perhaps most importantly, the Paperwork Reduction Act defines the “collection of information” to mean both:

- “answers to identical questions posed to, or identical reporting or recordkeeping requirements imposed on, ten or more persons”

- “answers to questions posed to agencies, instrumentalities, or employees of the United States which are to be used for general statistical purposes”

An official Guide to the Paperwork Reduction Act helpfully clarifies that you need clearance if you do anything that asks for “information to be sent to the government,” including “surveys, such as customer satisfaction or behavior surveys,” or “program evaluations, such as looking at the outcomes of a subsidized housing initiative for seniors,” or “research studies and focus groups with a set of the same questions.”

Indeed, it doesn’t seem to matter if the information requested is purely voluntary. From the same Guide, “Regardless of whether your collection is voluntary (i.e., the public is not required by law to provide information) or mandatory, the Paperwork Reduction Act treats the collection the same.”

***

In short, if you are at a government agency, and you want to do an A/B test to see which of two webpages might be easier to read, and you plan to survey 10 people to voluntarily say which one they prefer, you have triggered the Paperwork Reduction Act, and you may have to spend the next 9 months navigating a complicated bureaucratic process.

Or, if there’s a federally-sponsored program on reducing drug use, and you want to voluntarily survey 10 or more people as part of a study on whether the program worked, you will have to spend the next 9 months on the Paperwork Reduction Act process.

These requirements make no sense whatsoever. They directly inhibit government agencies from trying to improve the user experience or from studying whether a program works, even though one of the PRA’s goals is to “increase program efficiency and effectiveness”!

The contention that the PRA makes it harder to improve government isn’t just theoretical. It is a common complaint from former government insiders.

As Jen Pahlka (formerly the Deputy Chief Technology Officer of the US) says in her excellent book “Recoding America”:

The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau … recently asked OIRA (the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in the White House) for permission to continue some research it was already doing to improve its financial education programs…OIRA responded by posting the request to the Federal Register for two months of public comment. In other words, it sought feedback from the public on the CFPB’s plan to seek feedback from the public. In the meantime, no research would be allowed.

Absurd. Note that the logic here would lead to an infinite regress:

- “Can we seek feedback from the public on how to improve our programs?”

- “Maybe, but first we will have to separately seek feedback from the public on whether your request for feedback from the public might take too much time.”

- “But wait, what if that request takes too much time? Shouldn’t we first request feedback from the public on whether it makes sense to request feedback from the public before we can get feedback from the public?”

And so on.

As Pahlka also writes:

If you work in a federal agency trying to improve services for the public, and you want to, say, observe someone trying to use the current service to see what they find hard or confusing, chances are good that someone will tell you the PRA doesn’t allow for that, or that it might not allow for that, so you’ll need to get approval from OIRA. Sadly, the approval process requires so much time and effort that by the time approval comes, if it ever does, the project has moved on. Thus the PRA has often functioned as a ban on user research, the very practice that helps public servants reduce administrative burden on the public.

In other words, the PRA often inhibits the very thing it was supposed to do: reduce paperwork for the public.

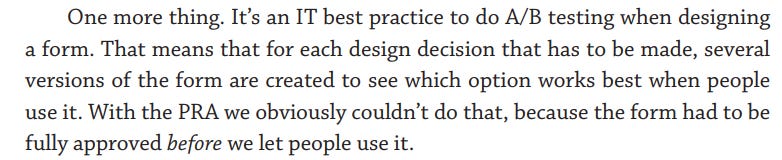

Mark Schwartz (former CIO for US Citizenship and Immigration Services) has also written about the perversity of the Paperwork Reduction Act. I’ll just screenshot the relevant passage from his book, rather than try to retype it:

As well, Joseph Condon has pointed out that the burdens of the Paperwork Reduction Act end up incentivizing federal agencies to avoid useful research altogether, thus harming their own mission:

In my experience as a former government researcher, I worked on projects involving PRA surveys that stretched out over several years to comply with the OIRA approval process for sampled surveys. I also worked on projects that, although they would have been substantially improved through the use of a survey, relied instead on individual and anecdotal interviews to draw conclusions. This delay, although purposeful, forces agencies to forgo useful information collection, delay actions that would support useful rulemaking, and inhibit program improvements that would meaningfully improve government functioning.

Again, the PRA’s ironic and perverse effect here is to stifle the PRA’s own goals to “minimize the cost to the Federal Government” and to “improve performance of agency missions.”

AVENUES FOR REFORM

How can we enable government agencies to reduce bureaucracy without creating even more bureaucracy? There are at least two pathways forward: Congress and OMB.

Congressional Reform of the Paperwork Reduction Act

I’ll start with the most radical ideas first, and then work down to more modest reforms.

Abolition

We could simply abolish the statutory scheme established in Sections 3506(c) and 3507. Federal agencies should not have to go through an elaborate process in order to take any step that might involve paperwork. They should be free to move forward with rules or practices that are within their congressional mandate, period.

Abolition sounds radical, but it’s actually not. Are there cases where federal agencies impose too much of a paperwork burden on members of the American public? Of course. But that doesn’t mean that the PRA review process actually improves things overall.

Indeed, as far as I can tell, there is literally no empirical evidence whatsoever that the benefits of PRA review outweigh the costs of the paperwork generated in the process!

No empirical evidence. None.

Add in the fact that agencies might avoid surveying citizens or doing program evaluations in cases where it isn’t worth 9 months of internal paperwork (or where such a delay would make the project untimely and pointless), and it is even less clear why we would think (even hypothetically) that the PRA’s benefits outweigh the costs.

Indeed, much of the “paperwork” that federal agencies require is actually due to congressional requirements, which means there’s not much either the agency or OMB/OIRA can do about it. As Stuart Shapiro found in his extensive expert report on the Paperwork Reduction Act, “The views of experts inside and outside of government, and the fact that much of the burden (because it is required by statute or by IRS) is not affected by the PRA, combine to indicate that burden-reduction is not a significant benefit of the PRA.”

Moreover, to the extent that paperwork or reporting requirements arise from an agency rule, there is a longstanding Executive Order (No. 12866) that requires OMB and OIRA to review proposed agency rules, and there should be plenty of opportunity to bring up paperwork during that review, if it matters at all.

Ultimately, there is no reason to think that adding 9+ months of Paperwork Reduction Act review creates any net benefits for anyone. It slows everything down, encourages agencies to stay away from surveys and program evaluations that would be untimely by the time they went through the PRA process, and creates an immense amount of paperwork for government agencies themselves.

The US government got along without the PRA process up until 1980. Yes, some folks in 1980 thought that paperwork was a problem, but often the remedy is worse than the disease. It may be time to go back.

Reforming the Statutory Triggers

If we don’t want to abolish the paperwork requirements altogether, there are much more modest—yet still meaningful—reforms that would be possible.

For example, as Andy Feldman (formerly an advisor to the Evidence Team at OMB) and Naomi Goldstein (formerly the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning, Research and Evaluation at HHS) wrote about this very issue, the Paperwork Reduction Act should be amended in two key ways:

- The statutory trigger should be 1,000+ people, rather than 10 as it is today. As they say, “No federal agency should need permission from OMB to undertake continuous improvement activities that involve small numbers and no significant burden to the American public.”

- Program evaluations (as contemplated by a number of federal laws, including the Evidence Act of 2018) should be entirely exempt if an agency has “strong standards and quality controls” to make sure that evaluations are rigorous, independent, etc.

These reforms make perfect sense, and would be easy to draft as amendments to the Paperwork Reduction Act. There is no evidence or reason to put the statutory trigger at 10 people rather than 1,000. In a nation of 330+ million people, it is absurd to make major national decisions as if we’re dealing with a rural village where hardly anyone lives.

There is even less reason that an agency should have to go through PRA review to do a study on, say, whether a drug abuse program, teen pregnancy prevention program, or STEM education program actually works. Such studies are basically required by the Evidence Act of 2018, and should be much more common, but the Paperwork Reduction Act is an absurd obstacle. As Feldman and Goldstein point out:

Let’s say Congress funds a new job training program for veterans. An important question for decision makers would be: Is it effective? . . . To answer the question, the agency may decide (or be required by Congress) to conduct a rigorous program evaluation. Because of the PRA, the evaluation may not be able to start for a year or more after the program begins. At that point, it is impossible to collect baseline data on veterans going into the program because the program has already begun. But baseline data are essential to accurately measure the change the program makes. The result is often either doing an evaluation that is not as strong as it could be or the agency decides to forgo an evaluation altogether . . . .

Talk about shooting yourself in the foot. That’s what the Paperwork Reduction Act does. In the name of making government more effective, the Act makes it harder or even impossible for agencies to conduct the very evaluations that would help them be more effective.

Voluntary vs. Involuntary

One perennially popular idea is that Congress could clarify that the Paperwork Reduction Act does not apply at all if the information request is voluntary (i.e., a request to fill out a survey or to participate in a program evaluation).

Indeed, this may not require much of an amendment, as there would have been no reason for Congress to worry about voluntary surveys and the like—the whole point of the Paperwork Reduction Act was to reduce the actual burden on the American people, not to limit voluntary surveys that people are free to ignore.

For example, Section 3505 says that federal agencies should have annual goals to “reduce information collection burdens imposed on the public.” And even more to the point, the main enforcement mechanism of the PRA (Section 3512) merely says that “no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information” if it doesn’t have a “valid control number” or if the agency fails to tell the person that they are “not required to respond” without a valid control number.

In other words, the goal here was to minimize burdens that are “imposed on the public,” and to prevent people from being subjected to penalties if the agency tries to “require” someone’s response in an invalid way. By contrast, nothing in the Paperwork Reduction Act suggests that a voluntary survey is a concern (let alone one about user experience itself!), since there would be no meaningful “burdens” or “penalties” in the first place.

All of that said, the “voluntary/involuntary” distinction has been suggested before, and met with some opposition. As Shapiro notes, some OIRA officials have pointed out that members of the public often don’t understand when a request is voluntary, and think that they are being required to answer. Moreover, an additional purpose of OIRA review is to make sure that informational requests are of high quality (including for statistical purposes), and that can be a useful check on agencies that try to deploy a survey that won’t deliver useful results.

Fair enough. Congress could add a PRA subsection explaining that voluntary reporting is not subject to the normal review requirements. And in any event, raising the statutory trigger to 1,000 people would cover almost all voluntary surveys and program evaluations.

Eliminate the Duplicative Public Comment Periods

As noted above, PRA approval happens only after two time periods in which the public is allowed to file comments—an initial 60-day period with the federal agency, and another 30-day period at OMB.

This is odd. I took Administrative Law with Elena Kagan when she was visiting at Harvard Law in 1999-2000, and I practiced administrative law for several years, but I don’t recall any other situation where there are two mandatory public comment periods. There is no need for this, especially given that the public submits comments on only 16% of the most onerous Paperwork Reduction Act notices anyway! Most of the time, literally no one cares about these Paperwork Reduction Act comment periods, and they are nothing more than a waste of time.

As both the Data Foundation’s 2020 report and Stuart Shapiro’s 2012 report both recommend, Congress should streamline these two comment periods into one.

OMB

OMB could continue its prior work to reduce the perverse burden of the Paperwork Reduction Act.

Delegate Review of Information Collection Below a Certain Threshold

One immensely valuable idea from Shapiro’s 2012 report is that OMB/OIRA should exempt or vastly streamline review for information collections that fall under a particular threshold.

For example, as of 2011, the vast majority of information collection requests from federal agencies would have created fewer than 10,000 hours of paperwork burden for the American public, and notably, only 7% of such requests got a public comment at all! Indeed, even for estimated burdens of up to 100,000 hours, only 12% got any public comments.

In other words: we are a nation of 330 million people, and a collective burden of under 10,000 or even 100,000 hours is so tiny that barely anyone cares, and there is obviously little benefit to federal agencies from getting next-to-zero feedback.

Thus, as the Shapiro memo recommended:

OMB should delegate to several pilot agencies review of information collections below a particular burden-hour threshold (recommended to be 100,000 hours) that do not raise novel legal, policy, or methodological issues. OMB should audit the results of delegations after two years; then, if abuse of delegation authority has not occurred, and time savings have resulted from the delegation, OMB should expand the delegation to all agencies. Regular audits of agency review processes should then follow.

Assuming that Shapiro is right that OMB has the authority to do so, OMB should have done this 10 years ago. It’s time they did so now.

Expand Generic Clearances and Fast Track Clearances

When famed legal scholar Cass Sunstein was OIRA Director, one of his key innovations was creating a system of generic clearances and fast track approvals.

What does that mean? Generic clearances are when an agency seeks approval to collect information in the same way, multiple times in the future.

According to what is now the official guide to the PRA, generic clearances are available (mostly for surveys) when an agency has multiple requests that are about similar information, that have a low paperwork burden, that don’t raise substantive policy issues, and that have details that aren’t known at the outset—e.g., almost always involving customer satisfaction surveys or focus group tests using conventional statistical methods of analysis.

If an agency gets a generic clearance for a particular user survey or the like, it can now use the “fast track” process for future occasions of that survey, which means no further public comment and a review in 5 business days.

All of this sounds like a great idea that could reduce the ongoing burden for federal agencies, although nowhere near as much as raising the floor to 1,000 people rather than 10.

Nonetheless, as Stuart Shapiro found in his 2018 report for the Administrative Conference of the United States, OIRA staff were surprised at how rarely federal agencies are using generic clearances for even for usability testing:

OIRA itself said the same thing in a 2018 notice:

[T]hese techniques have likely also faded in the consciousness of agencies, particularly with the turnover of agency personnel. There also appears to be very little use of the generic clearance and fast track processes to test the usability of forms or obtain feedback to improve agency websites, even though OIRA has indicated that usability testing is a good fit for these processes.

This isn’t actually very surprising. As Pahlka told me, even the “fast track” procedure can “spin up endless meetings and debates” on the agency side.

OMB/OIRA should explore ways to expand the availability and use of generic clearances that lead to later fast-track clearances, and to override agency hesitancy about using this process.

PS: The first image in this piece was generated by Dall-E on the first try, given a prompt asking for Sisyphus pushing a stack of paper up a mountain. The other images came from Midjourney, which, no matter what the prompt, refused to do anything other than depict the mountain itself as made out of paper.

[…] the amount of paperwork the government makes individuals, businesses, and itself process. Far from reducing paperwork, PRA has increased the amount of ink agencies have to generate. As a result, approval […]