If you care about evidence-based policy, one of your favorite moments in the past 20+ years is when the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018 was enacted. This Act is commonly known as the Evidence Act—after all, no one wants to repeat a long title all the time, and “FEBPA” is unpronounceable.

The Evidence Act created new evidentiary standards across all major federal agencies, including the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Dept. of Health and Human Services (which includes the National Institutes of Health, or NIH).

As discussed below, NSF seems to be taking the Evidence Act seriously, but NIH needs to substantially expand its efforts in order to comply with the law. As well, a better policy would be for each of HHS’s major operating divisions (including NIH, but also CDC, CMS, and FDA) to engage in its own evidence-building efforts.

***

Under the Evidence Act, agencies were all required to:

- Create a new position of Evaluation Officer. An agency’s Evaluation Officer is responsible for creating and implementing an “agency evaluation policy,” and for continually assessing the “coverage, quality, methods, consistency, effectiveness, independent, and balance of the portfolio of evaluations, policy research, and ongoing evaluation activities of the agency.”

- Create a new position of Chief Data Officer, with expertise in data management, data governance, and the like.

- Designate someone in the agency as a “statistical official to advice on statistical policy, techniques, and procedures.”

Agencies have been busy creating strategic plans for evaluation. These often take two forms: a yearly evaluation plan, and a longer-term “learning agenda” or “evidence-building plan” for the next several years. OMB just released a federal-wide dashboard listing all of these plans.

How do these plans look for NIH and NSF?

Let’s start with NSF. Its Annual Evaluation Plan for 2023 is here. It lists five major questions for the next year:

- Convergence Accelerator. In what ways does the Convergence Accelerator Innovation Training contribute to the emergence of new capacities among participating researchers to meet pressing societal needs?

- COVID pandemic. In what ways did the COVID pandemic influence the participation of different groups in the NSF portfolio of programs and activities, such as merit review?

- EPSCoR. How do Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) program funding strategies (infrastructure, co-funding, and outreach) contribute to increasing academic research competitiveness (ARC) across jurisdictions?

- Missing Millions. How can NSF help increase the participation of underrepresented groups in the STEM workforce?

- Partnerships. What are the benefits of receiving an award from a program supported by a partnership? How do these differ from benefits associated with awards from programs not supported by a partnership? What outputs and outcomes are associated with partnership programs? To what extent can these be attributed to the partnership programs? What improvements could make partnership programs more effective or easier to implement?

There are many other questions I’d want to know about NSF, but maybe those five questions are enough for one year. How about the longer-term plan?

NSF’s “Learning Agenda: FY 2022-FY 2026” is available here, and is 37 pages long. First, it laid out five main criteria for selecting evaluation questions, prioritizing evaluations that “fill a knowledge gap,” “have leadership support,” “have potential to support upcoming decisions,” “have potential for broad impacts,” and “are prioritized by NSF leadership.”

[It’s not clear why there are two prongs here for leadership support, but never mind.]

The document then lays out several overall strategic goals: “Empower STEM talent to fully participate in science and engineering”; “Create knowledge about our universe, our world, and ourselves”; “Benefit society by translating knowledge into solutions”; and, “Excel at NSF operations and management.”

Then, NSF lists several more specific questions under each strategic goal. I won’t list them all here, but they include some important agency-wide issues, such as how peer review (or “merit review” in NSF’s lingo) actually works. NSF then goes so far as to draw up initial ideas on a study plan (e.g., a meta-analysis followed by “well-matched comparison group designs”) for each of the questions.

I could quibble with some of the study questions and designs, but overall, NSF did put some thought into its overall strategic goals, and how various studies might help answer questions related to those goals. It isn’t awe-inspiring, but it isn’t zero.

Now for NIH….

NIH doesn’t have its own evaluation agenda (more on that in a moment!), but is instead bucketed within HHS. HHS has both a “FY 2023 Evaluation Plan,” and a “FY 2023-2026 Evidence-Building Plan.”

In the 2023 plan, NIH’s portion starts at page 37. It consists of a mere two evaluation questions:

- Assessing research outcomes for people who receive the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Predoctoral Training, with the goal of seeing whether this funding is “effective in preparing graduate students to transition to the next step in their pathway to a research career.”

- Assessing how to plan and monitor the “Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO)-wide Cohort,” a program that is trying to collect data from over 50,000 children and families.

This is . . . underwhelming.

NIH’s budget is more than 5 times NSF’s budget, and yet its evaluation plan for the next year is much less ambitious and substantive than NSF’s plan. I’m sure that amongst the many programs NIH funds, there are many more evaluation questions one could study over the next year.

Next, there’s the longer-term plan. Recall that NSF’s longer-term plan was 37 pages. The entirety of HHS, which includes not just NIH but FDA, CDC, CMS, and much more, merely has a 44-page plan for the next four years.

As one might expect, NIH’s portion is fairly small: the bottom of page 39 to the top of page 42 (about 3 pages of text in total). Over the next four years, NIH plans to assess 1) a set of recommendations that came out of a 2014 workshop on opioid treatment, 2) the Cancer Moonshot (NIH estimates an end date of 2027 for this), and 3) the data science portfolio at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

This isn’t a very impressive list of priorities. And unlike NSF, NIH does not describe any NIH-wide strategic priorities and goals that might help decide which evaluation questions are important.

In short, the NIH’s evaluation plans look quite thin compared to NSF, especially when you think about the overall scope of NIH’s many activities across 27 Institutes and Centers plus the Director’s Office.

A $45 billion agency requires far more evaluation and research than this, in order to be remotely compliant with the Evidence Act.

But is NIH to blame? No.

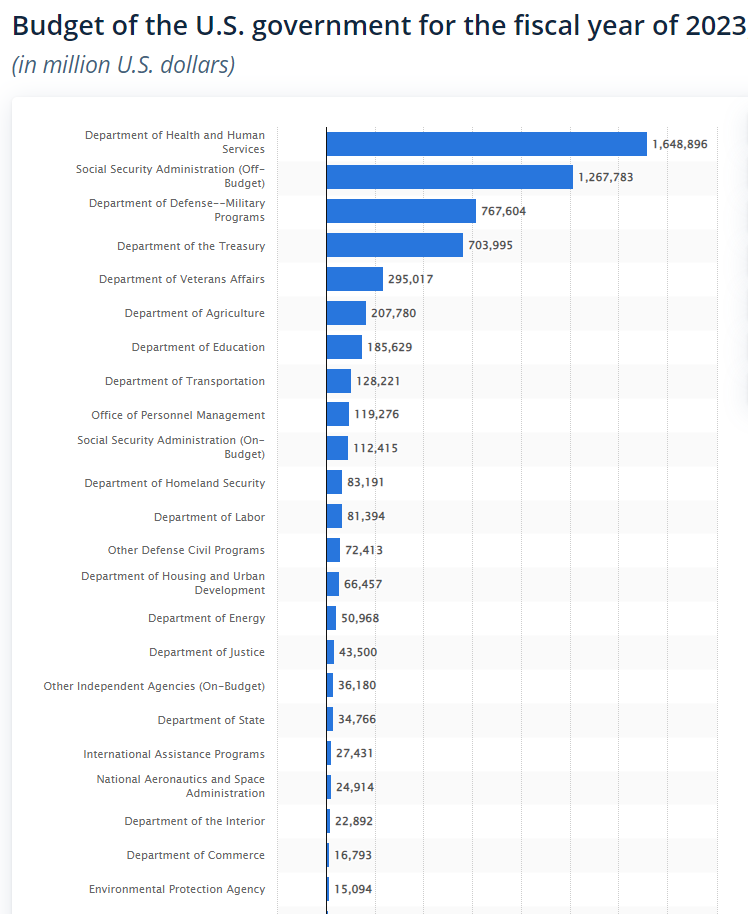

Instead, the federal structure is to blame. Under the Evidence Act, each agency is required to develop evaluation plans, etc. But not all agencies are equal. The Department of the Interior is one agency with about an $18 billion budget. HHS isn’t the same sort of “agency” at all: HHS has a budget of $1.6 trillion, and includes many operating divisions (or op-divs) such as NIH, FDA, CDC, and the big one: CMS.

In other words, look at this graph. It is very lopsided, to say the least.

Should all of these “agencies” be on the same footing with regards to the Evidence Act?

Absolutely not.

Why treat HHS the same as agencies that are around one percent as big, such as Interior or Commerce? HHS should have an overall Chief Evaluation Officer, sure, but should otherwise be split up for purposes of the Evidence Act. That is, each major operating division should have to hire its own Evaluation Officer, its own Chief Data Officer, etc., and should have to develop its own yearly evaluation plan and longer-term agenda.

There’s no reason to expect the same person to serve all of those functions for NIH, CMS, FDA, CDC, and more, with no designated point of contact at any of those divisions. Nor is there any reason to have one HHS-wide “learning agenda” that (if taken seriously) would be 1,000+ pages long and would cover many disparate activities about everything from drug approvals at FDA, to biomedical research at NIH, to hospital reimbursement at CMS. Instead, these major divisions should be directly responsible for fully participating in evaluation and data collection to the same degree as NSF.

As Kushal Kadakia and I recently argued in a Health Affairs article, the NIH should establish a Center for Experimentation/Innovation so as to evaluate important questions about science funding. But short of that, the least we could do is make sure that NIH (and any other major HHS division) has the resources and personnel to meet the Evidence Act’s requirements.

Indeed, at NIH, that might be a fairly straightforward task of reinvigorating and increasing the funding for the existing Office of Evaluation, Performance, and Reporting, whose website stopped publishing new evaluations several years ago (I’ve reached out to that office to ask if there are any more recent evaluations, but got no response).

As well, the Office of Portfolio Analysis at NIH has a 29-page Strategic Plan for 2021-2025 that is much more thoughtful and thorough than any of the Evidence Act documents, although the office mostly doesn’t seem to be addressed to “evaluation” per se (i.e., assessing the “effectiveness and efficiency” of various programs). To be sure, the office has published evaluations about racial and gender diversity, and it otherwise does great work on creating tools (e.g., citation metrics and AI/ML algorithms) that can measure the impact of research — but the Evidence Act would require that an agency actually use those tools to explore broader questions.

In sum, the Evidence Act and the thoughtful OMB guidance (see, e.g., here) requires much more than what HHS put together. Agencies are supposed to spend extensive time “engaging stakeholders, reviewing available evidence, developing questions, planning and undertaking activities, disseminating and using results, and refining questions based on evidence generated.” From the face of it, HHS did about 5% of what it should have done. We won’t fulfill the ambition of the Evidence Act unless major agencies like HHS take their duties seriously.