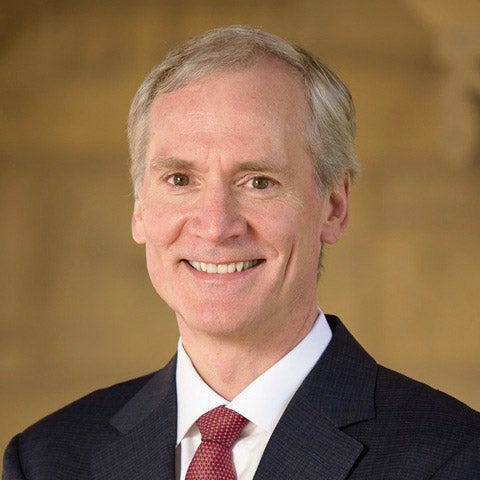

The President of Stanford (Marc Tessier-Lavigne) has recently come under investigation for a series of neuroscience papers that apparently had fake imagery in them. It remains to be seen how it will all play out.

What’s intriguing is that Tessier-Lavigne has been an author on 280 papers (according to PubMed). Fully 100 of the papers have been published since 2009, when he became Executive VP at Genentech (overseeing 1,400 scientists), then President of Rockefeller University, and finally President of Stanford.

Not to be overly cynical, but when someone is a high-level executive with thousands of people underneath him, it is unlikely that he meaningfully participated in 7+ top neuroscience studies per year for well over a decade. Instead, it seems likely that he has put his name on many papers where the work was entirely or almost entirely done by other people.

This is a well-known phenomenon in biomedicine, if not other fields as well, and it seems problematic at best. It’s how you end up with absurdities like the discredited French scholar Didier Raoult, who is listed as an author on 2,113 papers that came out of his lab.

Was Tessier-Lavigne actually responsible for creating any alleged fraud? I’m guessing not. It was probably other people far below him who were responsible.

And that’s often the excuse in such situations. When a famous behavioral economics paper was shown to be based on fraudulent data, for example, “four of the five authors” immediately announced that they “played no part in collecting the data.”

This tactic often works. After all, in team-based or lab-based work, there will usually be a rational division of labor. Someone who didn’t actually touch the data in question can correctly say that they couldn’t possibly have falsified the data.

Even so, I’m leaning towards a perhaps radical proposal:

If you sign your name to a paper, you are now professionally responsible for everything in that paper. If the data, analysis, or imagery later turns out to be fraudulent, you should bear the professional consequences even if you had nothing to do with it.

This may seem unfair, to be sure.

But it’s based on a principle from tort law: least cost avoider. In many cases where harm occurs (e.g., a product is sold that injures someone in an accident), the best thing to do is place liability on the person/institution who could have avoided the harm at the least cost, even if they technically did nothing “wrong.”

Because of their position, they can prevent future harm by taking precautions (such as manufacturing the product more safely) in a way that much more effectively avoids overall harm to everyone else. If you make them liable for future harm, they’ll take those precautions (and pass along the costs), and everyone will be better off.

An analogous idea might apply to scholarly literature and scientific research. Yes, one could imagine a world in which all readers are expected to reanalyze the data and figure out cases of potential fraud for themselves. But that would be enormously inefficient.

It would be far less of an overall cost to hold all individual authors of a paper responsible for ensuring that there is no research fraud. After all, they are:

- far fewer in number,

- far closer to the data and research in question,

- far more qualified than many readers, and

- far more responsible, in the sense that they agreed to work with and sign their names to someone else’s work in the first place.

Co-authors are optimally positioned to prevent research fraud (compared to readers or funders), and on that basis alone, should be held fully responsible.

On top of that, there would be another huge benefit: People would be highly incentivized to get more involved with their co-authors’ work, or else much less likely to sign their names to papers that they had little or nothing to do with.

After all, why take the risk of being professionally responsible for someone else’s misconduct? People would only sign their names to papers that they could meaningfully participate in and oversee.

As a result, you wouldn’t see nearly as many people with absurdly high publication and citation counts. The system overall would be more fair.

Less fraud, less unfairness. Win-win.